Why Short Term memory is a thing: forgetting as a creative act

Philosophy meets computer science

- tags

- tesla

Contents

Our new app TezLab pulls in data from your phone and your car to show you how to use your car better. It helps you understand your driving habits, how you use your battery, and shows you what other drivers are up to. In order to do this, we need fairly sophisticated ways of understanding the world.

Here, again, the role of the active faculty of forgetfulness, a kind of guardian, a supervisor responsible for maintaining the psychic, tranquility label. We immediately conclude that no happiness, no serenity, no hope, no pride, no enjoyment of the present moment could not exist without the possibility of forgetting. — Neitzsche, Geneology of Morals

Humans make math mistakes; computers don’t. Humans forget things, computers don’t. These are features of humans, and if we want to make computers smarter we need to understand the value in fuzzy thinking and forgetfulness. There are people who are capable of great feats of logic and memory, but evolution has instead selected for a goldilocks level of memory, remembering some things but not too much.

In our last discussion I wrote about the limits of binary logic, and how reality can be better represented by treating things not as true or false, but as more or less truthy. Knowing about knowing, being aware of the moment when your knowledge of the world went from being certain to being hazy, or acting on the moment where confusion becomes clear, actually makes understanding the world easier. It makes the math part of it a little more complicated but lets you design the types of “mistakes” you make. These “mistakes” can then be things that are self-correcting or otherwise helpful. Letting the computer make math “mistakes” helps.

In this post I’ll talk about how perfect memory actually makes things more complicated. Short Term memory — controlled forgetfulness — can simplifying reasoning and reduce cognitive load so that it’s less effort to reason more effectively about the world. Short Term and Long Term memory both have uses, but for many things techniques using short term memory out performs total recall.

Levels of Understanding

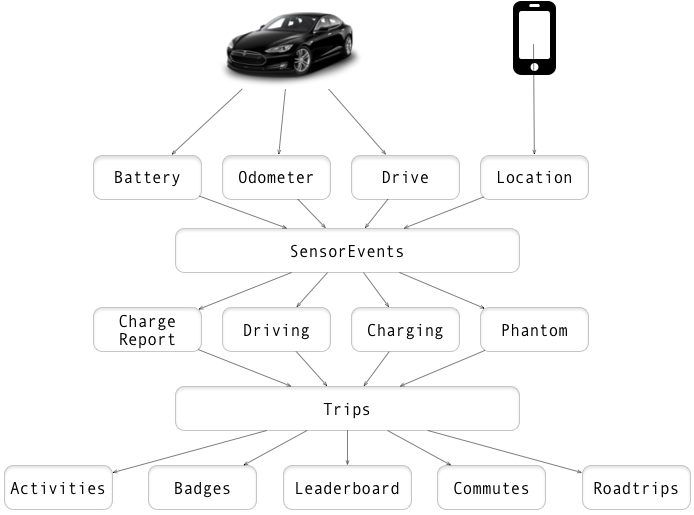

Before we get into the solution, lets talk a little bit about the problem we are trying to solve. Our app tracks data points from the car and the phone in order to show interesting things to the drivers. We have partial information, meaning we don’t always don’t get all the data that exists, so we need to figure out ways to fill in the gaps. We transform the raw data points to things that are understandable and hopefully actionable to the driver.

There are 4 main raw event streams that we get: phone location and speed, car odometer reading, car battery readings, and car transmission and location. These raw events are tied to a physical device that has a time and place, such as a phone or a car. As these raw events come in they get translated and digested.

The raw events get processed into SensorEvents. This is where we determine if the car is moving, or what the charge rate is as the battery warms up, things like that. Each of the different streams has a different type of Short Term memory that understands what the different events signify.

Sensor Events in turn get translated into drives, charges, and phantoms drives, and we can tell which phone was moving with which car. (In the case of multi-car multi-driver families, for example, all sorts of streams can get crossed and we’re actively tuning this now.) Each of these different types of trip has their own Short Term memory, which knows what to remember and what to forget as the events stream in from the other events.

Trips in turn get processed into charge reports, activities, and badges. Again with their own type of memory. And those in turn get organized into leaderboards, commutes, and road trips, which in turn get translated into etc. etc. etc.

As data comes in, we make a hypothesis about the world. This hypothesis colors and changes how we see the world. If the phone is moving, maybe the car is active. If the car is active maybe we monitor it. If the phone stops moving but we know the car is active we’ll keep monitoring. (For example, charging the car over night.) If we thought the car was active at some point, we’ll keep probing it even if we haven’t gotten a response in a while, hoping that if it gets back on the network we will capture as much data as possible.

Of course, maybe it’s just gone. Without the driver triggering us in some way, though motion of the app or starting it up, the server relaxes, winds down and quits pestering your car. Our idea of the world slowly fades away into forgetfulness as it doesn’t get updated.

Paying Attention

Our first level of forgetfulness is actually before remembering at all: it begins with choosing what we pay attention to. Attention itself is something that changes the world. You behave differently if someone is watching than when you are alone. In the case of the car it will go to sleep when it’s inactive reducing power consumption to a minimum. Once you use the app to see what the state of the car is, it partially powers up increasing drain.

We do nothing until the phone moves from one cell tower to another. If the phone is moving fast enough it triggers a check to with the car, which may or may not wake up. Based upon what we find the servers will perk up and start watching the car.

In our data then, we should expect gaps to occur for two reasons: we aren’t looking, or we aren’t seeing. We aren’t monitoring the car, or the car has stopped responding for some reason. Cell connectivity is spotty and it regularly takes 4–5 minutes for the car to connect back to the internet when I leave the underground parking for example. If we had access to the data — the car must know all of this stuff, and presumably there’s a database somewhere to query — but we don’t have access to any of that, and we need to build up what knowledge we can from staring at what is displayed in the app.

What triggers paying attention? Transmission, odometer activity, and battery power level changes. The phone wakes us from the slumber, where we peek a quiet eye at the car, and if we see something is happening we keep watching until it’s over. The two things we look for are if the driver is in the car or if the car is plugged in.

Time is an Illusion

The natural question is to ask what is happening right now? What’s going on in the present? The present though doesn’t actually exist. Is an event that happened 30 seconds ago the same as right now? 2 minutes? 15 minutes?

The first challenge we have is that data doesn’t come in real time. The latency between when the event occurred and we know about it can be upwards of 15 minutes. Streams come in a different rates, so when reasoning based upon these events sometimes we see the effects before we see the causes.

Our memory logic then needs to be able to separate when the event happened with the time of when it got the sample — there’s the timestamp of the event itself, and then the timestamp of when we know about it. If we learned something more about the past, then we need to reevaluate what we know about the present from that time forward forward.

We’re forced into some sort of imaginary time, where what we thought we knew then is different from what we now think we thought then. It’s a grammatical disaster. In the present, which is some blurry window of time between the past and the future, we are never really certain of what’s going on, things are constantly in flux as history gets revised.

The car’s API isn’t optimized for how we are using it. For example, there are 3 different endpoints we need to query to get what we need, and the sampling timestamps can get out of sync. The API doesn’t always return or give valid data, so there can be gaps between readings. If there’s a 5 minute gap between consecutive battery samples, and a different but overlapping gap between odometer readings, how do you calculate efficiency during that time? How detailed can you make the graph?

Luckily, the past doesn’t go anywhere. As events come in with greater or lesser latency “the present” dilates, our interpretations of the past changes but the underling reality doesn’t.

Optimizing Memory Length

Each stream’s memory needs are different. How you deal with gaps in certain values, or how you thing about ranges and fluctuations for each value is different. How do you decide the right way to remember things?

Lets take the battery memory for example. This type of memory interprets the raw data from the car’s battery. The data points we get are timestamp, battery range, battery state (disconnected, charging, charging paused, charging complete, etc) and rate of charge.

In the case of the battery readings generally we want to know when the battery is becomes active or is idling, if it’s charging, and what the range of battery readings are during that time. These are the things that we care about.

Lets say that we want to remember the battery range for 20 minutes. And if the battery state is “charging”, “charge complete”, “charging complete” then we want to remember that we are charging for 30 minutes. And then each sample we get in, we tell our memory object that we know the data points as a specific amount of time.

What happens with a 15 minute gap of data? In this example, since range and charging are remembered for more than 15 minutes, if we query the memory we “know” what the values to be. The gap can get smoothed over, and based upon how it expects the world to be, it can give an estimation of the value if you ask about it in the middle of the gap. If you are adding 1.5 mile of charge a minute, and 8 minutes have passed, you’ve probably added 12 miles.

On the other hand, If you were adding 1.5 miles of charge per minute, and 25 minutes have passed, we have no idea what has happened. Too much time has passed to know that detail, but if we might be able to guess that you are still charging, even if we don’t know amount that you’ve added.

If there’s a larger gap in time, lets say 2 hours, then there’s a gap in the memory that can’t be estimated, and when trying to tell the story of what happened there’s a blank spot.

A brief digression into a different domain

When thinking about optimizing these values a story from a different domain can help illuminate the trade offs. Let imagine how ants go and find food in the world. In their little ant brains they have a map of the world, and we want to know how long to remember where the food is. (This is normally used as example of emergent behavior, but lets instead look at their collective memory.)

Imagine a scenario where there’s one area near the nest that can be harvested every 7 days, after which is it’s empty until it grows back.

What’s the right level of detail for your map of the world? How long does it make sense for you to remember how much food was in a particular area? The temptation is to turn these ants into omniscient biologists, who not only make a super detailed map of the world and remember where things are, but also when they were there last, how often things grew, how this plant does in this soil, is the weather currently good for that plant etc.

This model of the world takes a huge amount of cognitive load to keep up to date, and is also likely to be suboptimal. There’s a big chance of obsessive compulsion, where the logic goes wrong and you get stuck in a loop, and there needs to be safeguard to avoid getting trapped into a local maximum.

This is not how evolution solved that problem. What it does instead is have the ants wander around, and they only remember where food is for a short period of time. If the knowledge is constantly reenforced by ants returning food, then the collectively remember where food is, but after a short period this knowledge fades away.

They basically just forget where the food was, and just have no information at all. After 7 days they would wander there by chance, and as an additional benefit they explore the whole environment. There’s less cognitive load and it also increases the likelihood to find some newly introduced novelty. The forgetting is both simpler to implement and is potentially a superior search algorithm.

Controlled forgetfulness simplifies the way of making sense of the world. Back to cars.

Remembering the future

Time is an illusion, the present is this fuzzy period of time between the past and the future. On further inspection, its not totally clear why the past is different from the future. The past is continually refining our idea of the present, which is constantly in flux, and the different possible pasts help us constrain the different possible futures.

There are situations where you want to ask memory about what it thinks will happen based upon what it knows now, in the future based upon the past and what it knows know. Charging and commuting are like this.

Lets imagine that you are at a super charger, and you want to know how long you need to stay there. We’ve rolled up the data to the point where we know you are started charging the car and haven’t stopped yet. We want to ask what do we remember/predict about the future: how fast is the car charging now, how fast will it be charging 10, 20, 30 minutes from now, how much range will be added to the car? If you plug into a 50 amp circuit or less its almost always a constant rate of charge, while supercharging rates vary based upon battery capacity, charge level, and temperature.

If we remember the battery range for 20 minutes, these memories of the future are entirely transient, they only exist when asked for, and are completely provisional.

Windows: how to know about change

In order to be aware of change we need to need to have some memory of context. Its not enough to remember the individual data points and compare them to each other, but we need to make sure that we have enough points to make a conclusion either way.

And given that data points don’t come in any regular interval, its not the last 10 points that matter, it’s the points in the last 10 minutes that matter.

For example, using the odometer as a data stream how can we decide if the car is moving or not? In our case we say we need at minimum of 5 data points in the last 20 minutes, and every data point needs to be the same. If that changes to true then the car is fixed in place. (This is used as a heuristic for when we are trying to figure out the start time of a trip.)

Highwater Marks

When you are actively trying to make sense of the world, forgetfulness is useful in order to simplify the process and to help keep you out of local maximums. But there are always things that make sense to remember forever. Car software versions, for example, should always go up. Odometers always go up.

One of the biggest use of this is when we “carve the past in stone”. There’s a point before which we don’t look further back, where we’ve decided, that’s the end of history, the present will never go back further than that. For different types of memories these timescales are vastly different. For things like battery readings it’s in hours, but if we are looking for battery charge reports, how far did that charge take you, it’s in days and week time scales.

When we are thinking about commutes, and figuring out where you home vs work is, these timescales are on months. It’s the closest thing to long term memory.

Short Term memory makes things simpler

Forgetfulness is a cheaper way to deal with change than making your analysis more sophisticated. The cost you pay is that you need to revisit things, but with a simpler model of the world you gain a lot of adaptability when dealing with a changing world that you have limiting knowledge of.

Robustly making sense of partial information is a lot more complicated then you might think.

Previously

Next